Emotional Intelligence in Action: We live and work in a reactive world. It seems to me that more and more companies give out badges of honor to those who take action first and fast. What’s wrong with that? It creates a culture of firefighting, where people expect the “first answer” rather than the right answer. I’m all about moving forward fast, but not every time and not at the expense of strategy.

We are constantly reacting to headlines. Our reactive culture has even infiltrated the stock market. If you pay attention to headlines you’ll see how in recent years they have been driving the markets. Oil spills, a crash, a callback, missing quarterly numbers, all of these headlines have driven stock prices down. In my view, the market has over reacted and then corrected. People have one data point, then over react to the news and make quick decisions. That’s usually when I buy, when there is an over reaction, it’s an opportunity to stay cool and try to capitalize. I am in no way qualified to give investment or trading advice, but I am qualified to give emotional investment advice.

I’ve been fortunate to be involved in researching and applying emotional intelligence (EI), which in general is a person’s ability to be aware of and manage their emotions, for just under two decades. What I became evident to me is that EI can be learned, and if you apply what you learn, you can make a huge positive impact on yourself and others. It started for me early on, I knew that there was something more to being successful rather than just traditional intelligence.

When I was studying the psychology of sport and performance at Springfield College’s Athletic Counseling program, I began to research EI. At the time, it had not taken off in corporate America yet. I decided to focus my thesis on this concept, but had limited empirical feedback about how to bridge the gap from research to practice. One summer, I was at the American Psychological Association’s conference in San Francisco and was walking on a random street. I happened to walk pass a person and recognized his face. It was Dr. Peter Salovey, the person who coined the term “emotional intelligence.”

Once I realized who it was, I turned around and asked him for a moment of his time. He gave me a lot more than that. He invited me to visit him at his office at Yale. He took the time to not only point my research in the right direction, but also to help me network with others in similar initiatives. Dr. Salovey is now the president of Yale University. His research had a large impact on my work and his wisdom and grace has had an even larger impact on me.

The business case for EI is clear and has been well researched. The basic case is that people who have high levels of EI are able to be more strategic about how they approach people and business. EI has been found to be a predictor of success in leaders and athletes. If you are interested in more specifics about the business case for EI, the EI Consortium is a solid starting place: www.eiconsortium.org.

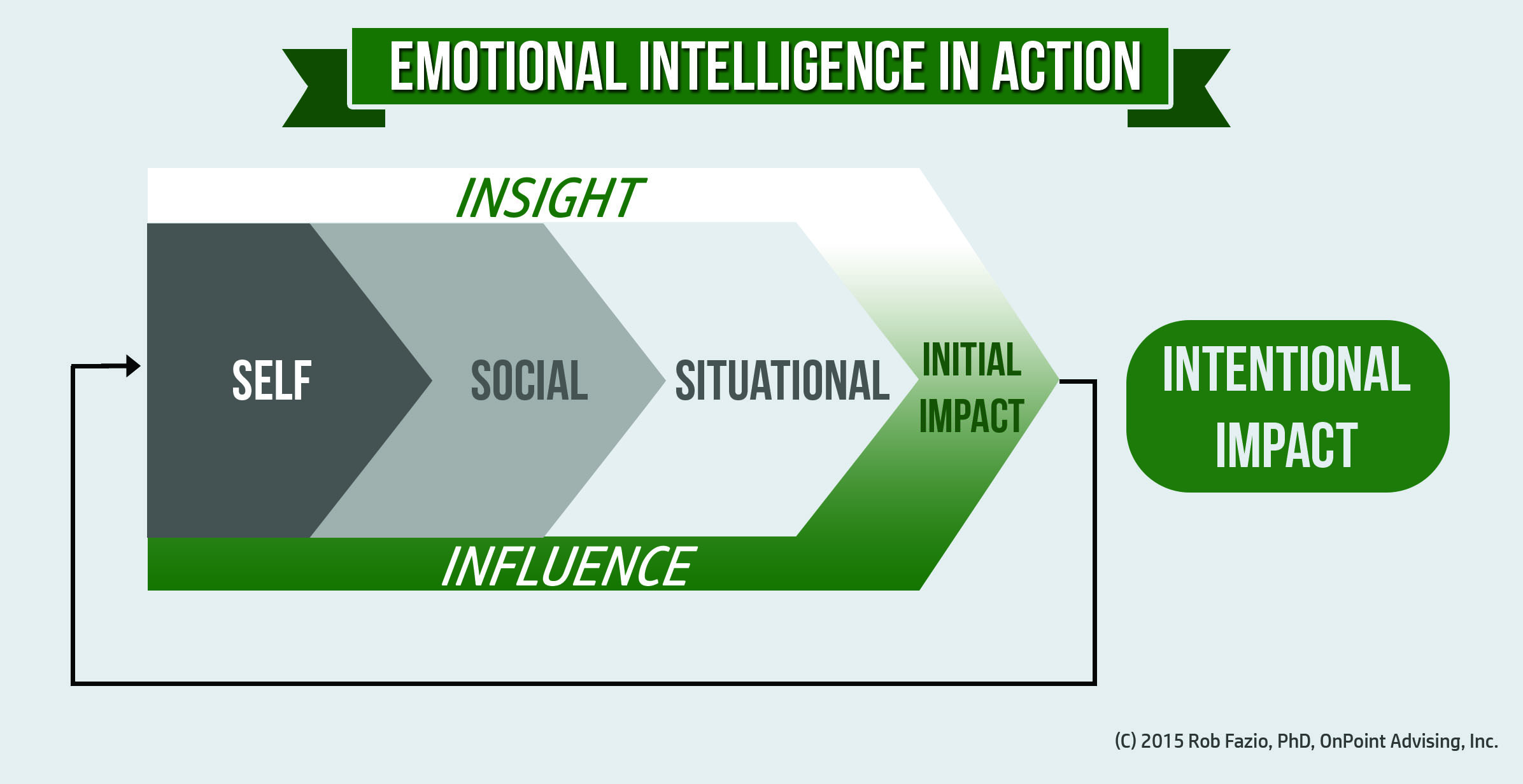

There are several theories of EI out there, many of them robust. My view is that EI does not have to be complicated; it has to be commonly stated. I created a framework for my clients that bridges theory to practice. I wanted to create something that is business focused and puts a premium on practical. The question I had was, what do people need in relation to EI to be successful? My answer is Emotional Intelligence in Action (Fazio, 2015).

Emotional Intelligence in Action (EIA) is the ability to leverage insight so you can intentionally influence. The focus is on taking intentional action toward what you want. EIA includes the integration of thinking, feeling, and acting so you can be strategic and get results. It is about taking your EI and putting it into practice. It is a combination of wisdom and action. It is developed over time with new experiences. Wisdom is about making smart choices and responding rather than reacting. Reactions are based on feelings and seem automatic, whereas responses are strategic and based on facts.

To take it a step further, feelings are the currency that runs the world. However warm and fuzzy or hokey as that sounds, it has been played time and time again in the work I do and the interactions I see around the world. When I have speaking engagements or advise people on the power of emotion in the workplace, I welcome them to challenge me. And trust me – clients on Wall Street, and top tier talent, challenge me on this point.

Here is my case. No matter what is at the surface, emotion is underneath it. I ask people why they do what they do? The usual response is for money. My response is what does money do for you? It buys you things, whether they are needed or not. What do these things do for you? They make you feel safe, important, or secure. Next I ask what religion does for you? They will say it gives you a place to go and a purpose, and my response is, yes it does, it gives you a feeling of community, connection, and meaning. Next I ask, what about power, success, or helping others? By this time, most people get it and understand. While there are multiple reasons for doing things, emotion is somewhere, whether people are aware of it or not. You are free to agree or disagree. All I ask is that you are open to learning how you can use emotion or it will use you.

In order to be successful over time, you need to focus on feelings and facts. Both have value and if you leave out one, the other will have a negative impact. People tend to overemphasize one or the other, especially in times when they are under pressure. In the moment, feelings can seem like facts and guide you in in a direction you don’t want to go. Feelings are what we associate with facts. For example if someone says something that upsets you, the fact is that they said something. Your feeling is the impact it had on you.

The important thing to remember that no matter what the situation and no matter what happens, all feelings come and all feelings go. At times they may seem intense and like they are going to knock you over, but they will always pass. We give power to feelings. Feeling are not negative or positive, they are neutral and just how we label our experiences. I like to think of it as the weather. Weather will always shift, and the more prepared you are and know what type of weather is coming, it has less of an impact on you. If it’s going to rain, you can bring an umbrella and dress accordingly. I’m not saying that rain doesn’t have the potential to bring people down, but we decide how long we stay down and if want to shift our response to the weather.

Have you ever “lost it” in a conversation? We all have. It’s called an emotional hijack. When there is a wave of emotion and it seems like you aren’t able to choose what you do next. An example of this may be when someone “gets under your skin” and you have an emotional outburst, also known as losing your composure. This is a common occurrence. Over time it can lead to people not viewing you as someone who is credible or in control. The good news is that with some insights and influence you can maintain your composure and be strategic about the decisions you make.

They key is to know your emotional triggers. Emotional triggers are the events, people, sayings, and situations that grab your emotional attention. We all have them and if aren’t aware of them, they have a big impact on how to react in the moment. An example of an emotional trigger is that person in meetings that keeps going off topic and makes the meeting run longer. One of my emotional triggers is injustice or manipulation. If someone is in a powerful position and they bully or treat others with less power poorly, that is a trigger for me. However, I know that I can protect myself by preparing for those situations and having strategies to deal with them.

The first step is to know your trigger, the second step is to respect it rather than avoid it, and third is to do something to help yourself take the power away from the emotion associated with the trigger. An example would be to remove yourself from the situation or to have something you can say to yourself to maintain your composure. For example, “this is just a temporary feeling and it will pass, and then I can decide what I want to do.”

Emotional Intelligence in Action Framework

The EIA framework places emphasis on achieving your desired outcome of your intentional impact. The three core elements of the framework are insight, influence, and impact. Insight and influence are the tools you use to help you reach the impact that you want (Intentional Impact). The three areas within insight and influence are self, social, and situational. Following are descriptions of the core elements outlined in detail.

Overview of Emotional Intelligence in Action

| Core Element | Domain | The ability to |

| Insight | Self Insight | have awareness of your emotions, thoughts, and how they influence your actions |

| Social Insight | read verbal and nonverbal cues, emotion in others, and your impact on others | |

| Situational Insight | recognize the power and politics in systems and the business context | |

| Influence | Self Influence | redirect and motivate yourself |

| Social Influence | engage in effective interpersonal interactions | |

| Situational Influence | initiate positive change to the current setting, culture, business, or industry | |

| Impact | Initial Impact | the outcome you get that may or may not match your intention |

| Intentional Impact | your desired outcome that is aligned with your intention |

The EIA framework is a cycle and is an ongoing process you can leverage until you are consistently achieving your intentional impact. At first, the initial impact you achieve may not be what you want or intend. Even worse, it may be the opposite of what you want. The purpose of having EW is to help you be more effective at being aware and taking strategic action.

Let’s work through an example of how this framework works in real life. The example I’ll use is an executive coaching engagement with a doctor who was the chief overseeing a critical area of a hospital. Let’s call him “Doc”. When I started working with him, I asked him what was most important to him and what he wanted to accomplish. He said that he wanted to be respected, credible, and build a high-performing team. That was his intention: respect, credibility, and his team’s high performance. I also asked him what he was doing to achieve what he wanted and how close he was. He responded by saying that he was close except that the team was not following his direct instruction. My goal here was to see what level of insight and influence he had.

To begin the process, I collected some anonymous feedback from his staff, his superiors, and peers. The messages in the feedback were clear. He was a leader that was feared rather than respected and there was a lot of fighting among his team. This is an example of a disconnect between his initial impact and his intentional impact. Once I built up some credibility and trust with Doc, I was able to get him to start with thinking about himself. I explained to him that there was a large gap between what he wanted and what he was getting, and it started with him.

Doc had very little self-insight, as he didn’t realize how his feelings of insecurity caused him to be overly directive. The short version of this is Doc worked on his ability to be aware when he was under pressure (self-insight) and catch himself in the moment and adapt his communication approach based on the situation and person (self-influence). The result was people started to respect him more, fear him less, and work more effectively together. In other words, through gaining awareness into how his feelings and thoughts were driving his behavior, he became more effective at being strategic and adapting his approach to leadership.

Emotional Hijack Practice

Let’s practice learning a little more about an emotional hijack. Picture yourself as someone who just got told that you needed to restructure your organization and let two people go. To make matters worse, this is the second time this year this has happened, and you were told that there would be no more layoffs. You also assured your team there would be no more layoffs. Put yourself in this situation and experience the situation attaching emotions and thoughts that you might have.

- What would your initial reaction be?

- Rate your approximate intensity of emotion(s) you feel? Use a 1 (low) to 10 (high) to identify your emotional intensity.

- What caused your level emotional reaction to the degree that you have indicated?

- What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of reacting this way?

- How might this affect your communication style in the moment and with your team?

- What impact may this have on your team’s performance? On your credibility?

- How can you most effectively lead yourself, your team, and your organization through this situation?

It may be the case that you are able to remain remarkably composed and see the positive in the scenario. For many people it is very difficult to not react and be less strategic with themselves and others when a situation has a high intensity of emotion. Over time and with experience you will become better at realizing when you are about to experience an emotional hijack. You’ll also get better at pulling yourself out of the emotional hijack. This series of questions can help you in all situations to be more strategic in how you manage your potential emotional highjacks.

Emotion is here to stay. You may as well start to obtain insight into yourself, other people, and situations that can help you be more effective at influencing. Getting blindsided by emotion causes unintended consequences. You won’t get it right every time, but I can guarantee you if you think before you act and act on what you think, you will be more successful at leading yourself and others.

(c) 2015 Rob Fazio, PhD, OnPoint Advising